DIMENSIONS:

490X 130 X 110mm.

W . 3010 grs.

Joan of Arc

| Saint Joan of Arc | |

|---|---|

Miniature (15th century)[1] | |

| Virgin and Martyr | |

| Born | 6 January c. 1412[2] Domrémy,Duchy of Bar,Kingdom of France[3] |

| Died | 30 May 1431 (aged approx. 19) Rouen,Normandy (thenunder English rule) |

| Veneratedin | Roman Catholic Church Anglican Communion[4] |

| Beatified | 18 April 1909,Notre Dame de ParisbyPope Pius X |

| Canonized | 16 May 1920,St. Peters Basilica, Rome byPope Benedict XV |

| Feast | 30 May |

| Attributes | armor, banner,sword |

| Patronage | France; martyrs; captives; military personnel; people ridiculed for their piety; prisoners; soldiers, women who have served in theWAVES(Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service); andWomens Army Corps |

| Native name | Jeanne dArc |

|---|---|

| Nickname(s) | La Pucelle The Maid of Orléans (French:La Pucelle dOrléans) |

| Allegiance | |

| Yearsof service | 1428–1430 |

| Battles/wars | Hundred Years War

|

| Signature |  |

Joan of Arc(French:Jeanne dArc,[5]IPA:[ʒan daʁk]; 6 January c. 1412[6]– 30 May 1431), nicknamed "The Maid of Orléans" (French:La Pucelle dOrléans), is considered a heroine of France for her role during theLancastrian phaseof theHundred Years Warand was canonized as aRoman Catholic saint. Joan of Arc was born toJacques dArcandIsabelle Romée, apeasantfamily, atDomrémyin north-east France. Joan said she received visions of theArchangelMichael,Saint Margaret, andSaint Catherine of Alexandriainstructing her to supportCharles VIIand recover France from English domination late in the Hundred Years War. The uncrowned King Charles VII sent Joan to thesiege of Orléansas part of a relief mission. She gained prominence after the siege was lifted only nine days later. Several additional swift victories led to Charles VIIs coronation atReims. This long-awaited event boosted French morale and paved the way for the final French victory.

On 23 May 1430, she was captured atCompiègneby theBurgundian faction, which was allied with the English. She was later handed over to the English[7]and put on trial by the pro-English Bishop of BeauvaisPierre Cauchonon a variety of charges.[8]After Cauchon declared her guilty she wasburned at the stakeon 30 May 1431, dying at about nineteen years of age.[9]

In 1456, an inquisitorial court authorized byPope Callixtus IIIexamined the trial, debunked the charges against her, pronounced her innocent, and declared her amartyr.[9]In the 16th century she became a symbol of theCatholic League, and in 1803 she was declared a national symbol of France by the decision ofNapoleonBonaparte.[10]She wasbeatifiedin 1909 andcanonizedin 1920. Joan of Arc is one of the nine secondarypatron saintsof France, along withSaint Denis,Saint Martin of Tours,Saint Louis,Saint Michael,Saint Rémi,Saint Petronilla,Saint RadegundandSaint Thérèse of Lisieux.

Joan of Arc has remained a popular figure in literature, painting, sculpture, and other cultural works since the time of her death, and many famous writers, filmmakers and composers have created works about her.Cultural depictions of herhave continued in films, theater, television, video games, music, and performances to this day.

Background

TheHundred Years Warhad begun in 1337 as aninheritance dispute over the French throne, interspersed with occasional periods of relative peace. Nearly all the fighting had taken place in France, and the English armys use ofchevauchéetactics (destructive "scorched earth" raids) had devastated the economy.[11]TheFrench populationhad not recovered to its size previous to theBlack Deathof the mid-14th century, and its merchants were isolated from foreign markets. Prior to the appearance of Joan of Arc, the English had nearly achieved their goal of a dual monarchy under English control and the French army had not achieved any major victories for a generation. In the words of DeVries, "The kingdom of France was not even a shadow of its thirteenth-century prototype."[12]

The French king at the time of Joans birth,Charles VI, suffered from bouts of insanity[13]and was often unable to rule. The kings brotherLouis,Duke of Orléans, and the kings cousinJohn the Fearless,Duke of Burgundy, quarreled over the regency of France and the guardianship of the royal children. This dispute included accusations that Louis was having an extramarital affair with the queen,Isabeau of Bavaria, and allegations that John the Fearless kidnapped the royal children.[14]The conflict climaxed with the assassination of the Duke of Orléans in 1407 on the orders of the Duke of Burgundy.[15][16]

The young Charles of Orléans succeeded his father as duke and was placed in the custody of his father-in-law, theCount of Armagnac. Their faction became known as the"Armagnac" faction, and the opposing party led by the Duke of Burgundy was called the"Burgundian faction".Henry V of Englandtook advantage of these internal divisions when he invaded the kingdom in 1415, winning a dramaticvictory at Agincourton 25 October and subsequently capturing many northern French towns.[17]In 1418Pariswas taken by the Burgundians, who massacred the Count of Armagnac and about 2,500 of his followers.[18]The future French king,Charles VII, assumed the title ofDauphin—the heir to the throne—at the age of fourteen, after all four of his older brothers had died in succession.[19]His first significant official act was to conclude a peace treaty with the Duke of Burgundy in 1419. This ended in disaster when Armagnac partisans assassinated John the Fearless during a meeting under Charless guarantee of protection. The new duke of Burgundy,Philip the Good, blamed Charles for the murder and entered into an alliance with the English. The allied forces conquered large sections of France.[20]

In 1420 the queen of France,Isabeau of Bavaria, signed theTreaty of Troyes, which granted the succession of the French throne toHenry Vand his heirs instead of her son Charles. This agreement revived suspicions that the Dauphin may have been the illegitimate product of Isabeaus rumored affair with the late duke of Orléans rather than the son of King Charles VI.[21]Henry V and Charles VI died within two months of each other in 1422, leaving an infant,Henry VI of England, the nominal monarch of both kingdoms. Henry Vs brother,John of Lancaster, 1st Duke of Bedford, acted asregent.[22]

By the time Joan of Arc began to influence events in 1429, nearly all of northern France and some parts of the southwest were under Anglo-Burgundian control. The English controlled Paris andRouenwhile the Burgundian faction controlledReims, which had served as the traditional coronation site for French kings since 816. This was an important consideration since neither claimant to the throne of France had been officially crowned yet. In 1428 the English had begun the siege of Orléans, one of the few remaining cities still loyal to Charles VII and an important objective since it held a strategic position along theLoireRiver, which made it the last obstacle to an assault on the remainder of the French heartland. In the words of one modern historian, "On the fate of Orléans hung that of the entire kingdom."[23]No one was optimistic that the city could long withstand the siege.[24]For generations, there had been prophecies in France which promised France would be saved by a virgin from the "borders of Lorraine" "who would work miracles" and "that France will be lost by a woman and shall thereafter be restored by a virgin".[25]The second prophecy predicating France would be "lost" by a woman was taken to refer to Isabeaus role in signing the Treaty of Troyes.[26]

Life

Joan was the daughter ofJacques dArcandIsabelle Romée[27]inDomrémy, a village which was then in the French part of theduchy of Bar.[28]Joans parents owned about 50 acres (20 hectares) of land and her father supplemented his farming work with a minor position as a village official, collecting taxes and heading the local watch.[29]They lived in an isolated patch of eastern France that remained loyal to the French crown despite being surrounded by pro-Burgundian lands. Several local raids occurred during her childhood and on one occasion her village was burned. Joan was illiterate and it is believed that her letters were dictated by her to scribes and she signed her letters with the help of others.[30]

At her trial, Joan stated that she was about nineteen years old, which implies she thought she was born around 1412. She later testified that she experienced her first vision in 1425 at the age of 13, when she was in her "fathers garden"[31]and saw visions of figures she identified asSaint Michael,Saint Catherine, andSaint Margaret, who told her to drive out the English and bring the Dauphin to Reims for his coronation. She said she cried when they left, as they were so beautiful.[32]

At the age of sixteen, she asked a relative named Durand Lassois to take her to the nearby town ofVaucouleurs, where she petitioned the garrison commander,Robert de Baudricourt, for an armed escort to bring her to the French Royal Court atChinon. Baudricourts sarcastic response did not deter her.[33]She returned the following January and gained support from two of Baudricourts soldiers:Jean de MetzandBertrand de Poulengy.[34]According to Jean de Metz, she told him that "I must be at the Kings side... there will be no help (for the kingdom) if not from me. Although I would rather have remained spinning [wool] at my mothers side... yet must I go and must I do this thing, for my Lord wills that I do so."[35]Under the auspices of Metz and Poulengy, she was given a second meeting, where she made a prediction about a military reversal at theBattle of Rouvraynear Orléans several days before messengers arrived to report it.[36]According to theJournal du Siége d’Orléans,which portrays Joan as a miraculous figure, Joan came to know of the battle through "grace divine" while tending her flocks in Lorraine and used this divine revelation to persuade Baudricort to take her to the Dauphin.[37]

Rise

Robert de Baudricourt granted Joan an escort to visit Chinon after news from Orleans confirmed her assertion of the defeat. She made the journey through hostile Burgundian territory disguised as a male soldier,[38]a fact which would later lead to charges of "cross-dressing" against her, although her escort viewed it as a normal precaution. Two of the members of her escort said they and the people of Vaucouleurs provided her with this clothing, and had suggested it to her.[39]

After arriving at the Royal Court she impressed Charles VII during a private conference. During this time Charles mother-in-lawYolande of Aragonwas planning to finance a relief expedition toOrléans. Joan asked for permission to travel with the army and wear protective armor, which was provided by the Royal government. She depended on donated items for her armor, horse, sword, banner, and other items utilized by her entourage. Historian Stephen W. Richey explains her attraction to the royal court by pointing out that they may have viewed her as the only source of hope for a regime that was near collapse:

After years of one humiliating defeat after another, both the military and civil leadership of France were demoralized and discredited. When the Dauphin Charles granted Joans urgent request to be equipped for war and placed at the head of his army, his decision must have been based in large part on the knowledge that every orthodox, every rational option had been tried and had failed. Only a regime in the final straits of desperation would pay any heed to an illiterate farm girl who claimed that the voice of God was instructing her to take charge of her countrys army and lead it to victory.[40]

Upon her arrival, Joan effectively turned the longstanding Anglo-French conflict into a religious war,[41]a course of action that was not without risk. Charles advisers were worried that unless Joansorthodoxycould be established beyond doubt—that she was not a heretic or a sorceress—Charles enemies could easily make the allegation that his crown was a gift from the devil. To circumvent this possibility, the Dauphin ordered background inquiries and a theological examination atPoitiersto verify her morality. In April 1429, the commission of inquiry "declared her to be of irreproachable life, a good Christian, possessed of the virtues of humility, honesty and simplicity."[41]The theologians at Poitiers did not render a decision on the issue of divine inspiration; rather, they informed the Dauphin that there was a "favorable presumption" to be made on the divine nature of her mission. This was enough for Charles, but they also stated that he had an obligation to put Joan to the test. "To doubt or abandon her without suspicion of evil would be to repudiate theHoly Spiritand to become unworthy of Gods aid", they declared.[42]They recommended that her claims should be put to the test by seeing if she could lift the siege ofOrléansas she had predicted.[citation needed]

She arrived at thebesieged city of Orléanson 29 April 1429.Jean dOrléans, the acting head of the ducal family of Orléans on behalf of his captive half-brother, initially excluded her fromwar councilsand failed to inform her when the army engaged the enemy.[43]However, his decision to exclude her did not prevent her presence at most councils and battles.[citation needed]

The extent of her actual military participation and leadership is a subject of debate among historians. On the one hand, Joan stated that she carried her banner in battle and had never killed anyone,[44]preferring her banner "forty times" better than a sword;[45]and the army was always directly commanded by a nobleman, such as the Duke of Alençon for example. On the other hand, many of these same noblemen stated that Joan had a profound effect on their decisions since they often accepted the advice she gave them, believing her advice was divinely inspired.[46]In either case, historians agree that the army enjoyed remarkable success during her brief time with it.[47]

Military campaigns

The appearance of Joan of Arc at Orléans coincided with a sudden change in the pattern of the siege. During the five months before her arrival, the defenders had attempted only one offensive assault, which had ended in defeat. On 4 May, however, the Armagnacs attacked and captured the outlying fortress ofSaint Loup(bastille de Saint-Loup), followed on 5 May by a march to a second fortress calledSaint-Jean-le-Blanc, which was found deserted. When English troops came out to oppose the advance, a rapid cavalry charge drove them back into their fortresses, apparently without a fight. The Armagnacs then attacked and captured an English fortress built around a monastery calledLes Augustins. That night, Armagnac troops maintained positions on the south bank of the river before attacking the main English stronghold, called"les Tourelles", on the morning of 7 May.[49]Contemporaries acknowledged Joan as the heroine of the engagement. She was wounded by an arrow between the neck and shoulder while holding her banner in the trench outside les Tourelles, but later returned to encourage a final assault that succeeded in taking the fortress. The English retreated from Orléans the next day, and the siege was over.[citation needed]

At Chinon and Poitiers, Joan had declared that she would provide a sign at Orléans. The lifting of the siege was interpreted by many people to be that sign, and it gained her the support of prominent clergy such as theArchbishop of Embrunand the theologianJean Gerson, both of whom wrote supportive treatises immediately following this event.[50]To the English, the ability of this peasant girl to defeat their armies was regarded as proof that she was possessed by the Devil; the British medievalist Beverly Boyd noted that this charge was not just propaganda, and was sincerely believed since the idea that God was supporting the French via Joan was distinctly unappealing to an English audience.[51]

The sudden victory at Orléans also led to many proposals for further offensive action. Joan persuaded Charles VII to allow her to accompany the army with DukeJohn II of Alençon, and she gained royal permission for her plan to recapture nearby bridges along the Loire as a prelude to an advance on Reims and the coronation of Charles VII. This was a bold proposal because Reims was roughly twice as far away as Paris and deep within enemy territory.[52]The English expected an attempt to recapture Paris or an attack on Normandy.[citation needed]

The Duke of Alençon accepted Joans advice concerning strategy. Other commanders including Jean dOrléans had been impressed with her performance at Orléans and became her supporters. Alençon credited her with saving his life at Jargeau, where she warned him that a cannon on the walls was about to fire at him.[53]During the same siege she withstood a blow from a stone that hit her helmet while she was near the base of the towns wall. The army tookJargeauon 12 June,Meung-sur-Loireon 15 June, andBeaugencyon 17 June.[citation needed]

The English army withdrew from the Loire Valley and headed north on 18 June, joining with an expected unit of reinforcements under the command of SirJohn Fastolf. Joan urged the Armagnacs to pursue, and the two armies clashed southwest of the village of Patay. Thebattle at Pataymight be compared toAgincourtin reverse. The French vanguard attacked a unit of Englisharcherswho had been placed to block the road. A rout ensued that decimated the main body of the English army and killed or captured most of its commanders. Fastolf escaped with a small band of soldiers and became the scapegoat for the humiliating English defeat. The French suffered minimal losses.[54]

The French army leftGienon 29 June on themarch toward Reimsand accepted the conditional surrender of the Burgundian-held city ofAuxerreon 3 July. Other towns in the armys path returned to French allegiance without resistance.Troyes, the site of the treaty that tried to disinherit Charles VII, was the only one to put up even brief opposition. The army was in short supply of food by the time it reached Troyes. But the army was in luck: a wandering friar named Brother Richard had been preaching about the end of the world at Troyes and convinced local residents to plant beans, a crop with an early harvest. The hungry army arrived as the beans ripened.[55]Troyes capitulated after a bloodless four-day siege.[56]

Reims opened its gates to the army on 16 July 1429. The coronation took place the following morning. Although Joan and the Duke of Alençon urged a prompt march on Paris, the royal court preferred to negotiate a truce with Duke Philip of Burgundy. The duke violated the purpose of the agreement by using it as a stalling tactic to reinforce the defense of Paris.[57]The French army marched through towns near Paris during the interim and accepted several peaceful surrenders. The Duke of Bedford led an English force and confronted the French army in a standoff at the battle of Montépilloy on 15 August. The Frenchassault at Parisensued on 8 September. Despite a wound to the leg from acrossbow bolt, Joan remained in the inner trench of Paris until she was carried back to safety by one of the commanders.[58]The following morning the army received a royal order to withdraw. Most historians blame FrenchGrand ChamberlainGeorges de la Trémoillefor the political blunders that followed the coronation.[59]In October, Joan was with the royal army when ittook Saint-Pierre-le-Moûtier, followed by an unsuccessful attempt to takeLa-Charité-sur-Loirein November and December. On 29 December, Joan and her family were ennobled by Charles VII as a reward for her actions.[citation needed]

Ruin of the great hall atChâteau de Chinonwhere Joan met future King Charles VII. The castles only remaining intact tower, now known as the Joan of Arc Tower, has been turned into a museum dedicated to her.

Entrance of Joan of Arc into Reims in 1429, painting byJan Matejko

The inner keep atBeaugencyis one of the few surviving fortifications from Joans campaigns. English defenders retreated to the tower at upper right after the French breached the town wall.

Notre-Dame de Reims, traditional site of French coronations. The structure had additional spires prior to a 1481 fire.

Capture

A truce with England during the following few months left Joan with little to do. On 23 March 1430, she dictated a threatening letter to theHussites, a dissident group which had broken with the Catholic Church on a number of doctrinal points and had defeated several previous crusades sent against them. Joans letter promises to "remove your madness and foul superstition, taking away either your heresy or your lives."[60]Joan, an ardent Catholic who hated all forms of heresy together with Islam also sent a letter challenging the English to leave France and go with her to Bohemia to fight the Hussites, an offer that went unanswered.[61]

The truce with England quickly came to an end. Joan traveled toCompiègnethe following May to help defend the city against anEnglish and Burgundian siege. On 23 May 1430 she was with a force that attempted to attack the Burgundian camp at Margny north of Compiègne, but was ambushed and captured.[62]When the troops began to withdraw toward the nearby fortifications of Compiègne after the advance of an additional force of 6,000 Burgundians,[62]Joan stayed with the rear guard. Burgundian troops surrounded the rear guard, and she was pulled off her horse by anarcher.[63]She agreed to surrender to a pro-Burgundian nobleman named Lionel of Wandomme, a member ofJean de Luxembourgs unit.[citation needed]

Joan was imprisoned by the Burgundians at Beaurevoir Castle. She made several escape attempts, on one occasion jumping from her 70-foot (21m) tower, landing on the soft earth of a dry moat, after which she was moved to the Burgundian town ofArras.[64]The English negotiated with their Burgundian allies to transfer her to their custody, with BishopPierre CauchonofBeauvais, an English partisan, assuming a prominent role in these negotiations and her later trial.[65]The final agreement called for the English to pay the sum of 10,000livres tournois[66]to obtain her from Jean de Luxembourg, a member of the Council of Duke Philip of Burgundy.[citation needed]

The English moved Joan to the city of Rouen, which served as their main headquarters in France. Historian Pierre Champion notes that the Armagnacs attempted to rescue her several times by launching military campaigns toward Rouen while she was held there. One campaign occurred during the winter of 1430–1431, another in March 1431, and one in late May shortly before her execution. These attempts were beaten back.[67]Champion also quotes 15th-century sources that say Charles VII threatened to "exact vengeance" upon Burgundian troops whom his forces had captured and upon "the English and women of England" in retaliation for their treatment of Joan.[68]

Trial

The trial forheresywas politically motivated. The tribunal was composed entirely of pro-English and Burgundian clerics, and overseen by English commanders including the Duke of Bedford and the Earl of Warwick.[69]In the words of the British medievalist Beverly Boyd, the trial was meant by the English Crown to be "...a ploy to get rid of a bizarre prisoner of war with maximum embarrassment to their enemies".[51]Legal proceedings commenced on 9 January 1431 atRouen, the seat of the English occupation government.[70]The procedure was suspect on a number of points, which would later provoke criticism of the tribunal by the chief inquisitor who investigated the trial after the war.[71]

Under ecclesiastical law, Bishop Cauchon lackedjurisdictionover the case.[72]Cauchon owed his appointment to his partisan support of the English Crown, which financed the trial. The low standard of evidence used in the trial also violated inquisitorial rules.[73]Clerical notary Nicolas Bailly, who was commissioned to collect testimony against Joan, could find no adverse evidence.[74]Without such evidence the court lacked grounds to initiate a trial. Opening a trial anyway, the court also violated ecclesiastical law by denying Joan the right to a legal adviser. In addition, stacking the tribunal entirely with pro-English clergy violated the medieval Churchs requirement that heresy trials be judged by an impartial or balanced group of clerics. Upon the opening of the first public examination, Joan complained that those present were all partisans against her and asked for "ecclesiastics of the French side" to be invited in order to provide balance. This request was denied.[75]

The Vice-Inquisitor of Northern France (Jean Lemaitre) objected to the trial at its outset, and several eyewitnesses later said he was forced to cooperate after the English threatened his life.[76]Some of the other clergy at the trial were also threatened when they refused to cooperate, including a Dominican friar named Isambart de la Pierre.[77]These threats, and the domination of the trial by a secular government, were violations of the Churchs rules and undermined the right of the Church to conduct heresy trials without secular interference.[citation needed]

The trial record contains statements from Joan that the eyewitnesses later said astonished the court, since she was an illiterate peasant and yet was able to evade the theological pitfalls the tribunal had set up to entrap her. The transcripts most famous exchange is an exercise in subtlety: "Asked if she knew she was in Gods grace, she answered, If I am not, may God put me there; and if I am, may God so keep me."[78]The question is a scholarly trap. Church doctrine held that no one could be certain of being in Gods grace. If she had answered yes, then she would have been charged with heresy. If she had answered no, then she would have confessed her own guilt. The court notary Boisguillaume later testified that at the moment the court heard her reply, "Those who were interrogating her were stupefied."[79]

Several members of the tribunal later testified that important portions of the transcript were falsified by being altered in her disfavor. Under Inquisitorial guidelines, Joan should have been confined in anecclesiasticalprison under the supervision of female guards (i.e., nuns). Instead, the English kept her in asecularprison guarded by their own soldiers. Bishop Cauchon denied Joans appeals to theCouncil of Baseland the Pope, which should have stopped his proceeding.[80]

The twelve articles of accusation which summarized the courts findings contradicted the already doctored court record.[81]The illiterate defendant signed anabjurationdocument that she did not understand under threat of immediate execution. The court substituted a different abjuration in the official record.[82]

Cross-dressing charge

Heresywas acapital crimeonly for a repeat offense, therefore a repeat offense of "cross-dressing" was now arranged by the court, according to the eyewitnesses. Joan agreed to wear feminine clothing when she abjured, which created a problem. According to the later descriptions of some of the tribunal members, she had previously been wearing male (i.e. military) clothing in prison because it gave her the ability to fasten her hosen, boots and tunic together into one piece, which deterred rape by making it difficult to pull her hosen off. She was evidently afraid to give up this outfit even temporarily because it was likely to be confiscated by the judge and she would thereby be left without protection.[83][84]A womans dress offered no such protection. A few days after her abjuration, when she was forced to wear a dress, she told a tribunal member that "a great English lord had entered her prison and tried to take her by force."[85]She resumed male attire either as a defense against molestation or, in the testimony of Jean Massieu, because her dress had been taken by the guards and she was left with nothing else to wear.[86]

Her resumption of male military clothing was labeled a relapse into heresy for cross-dressing, although this would later be disputed by the inquisitor who presided over the appeals court that examined the case after the war. Medieval Catholic doctrine held that cross-dressing should be evaluated based on context, as stated in theSumma TheologicabySt. Thomas Aquinas, which says that necessity would be a permissible reason for cross-dressing.[87]This would include the use of clothing as protection against rape if the clothing would offer protection. In terms of doctrine, she had been justified in disguising herself as a pageboy during her journey through enemy territory, and she was justified in wearing armor during battle and protective clothing in camp and then in prison. TheChronique de la Pucellestates that it deterred molestation while she was camped in the field. When her soldiers clothing wasnt needed while on campaign, she was said to have gone back to wearing a dress.[88]Clergy who later testified at the posthumous appellate trial affirmed that she continued to wear male clothing in prison to deter molestation and rape.[83]

Joan referred the court to the Poitiers inquiry when questioned on the matter. The Poitiers record no longer survives, but circumstances indicate the Poitiers clerics had approved her practice.[89]She also kept her hair cut short through her military campaigns and while in prison. Her supporters, such as the theologianJean Gerson, defended her hairstyle for practical reasons, as did Inquisitor Brehal later during the appellate trial.[90]Nonetheless, at the trial in 1431 she was condemned and sentenced to die. Boyd described Joans trial as so "unfair" that the trial transcripts were later used as evidence for canonizing her in the 20th century.[51]

Execution

Eyewitnesses described the scene of theexecution by burningon 30 May 1431. Tied to a tall pillar at the Vieux-Marché in Rouen, she asked two of the clergy, Fr Martin Ladvenu and Fr Isambart de la Pierre, to hold acrucifixbefore her. An English soldier also constructed a small cross that she put in the front of her dress. After she died, the English raked back the coals to expose her charred body so that no one could claim she had escaped alive. They then burned the body twice more, to reduce it to ashes and prevent any collection of relics, and cast her remains into theSeineRiver.[91]The executioner, Geoffroy Thérage, later stated that he "greatly feared to be damned."[92]

Posthumous events

The Hundred Years War continued for twenty-two years after her death. Charles VII retained legitimacy as the king of France in spite of a rival coronation held forHenry VIatNotre-Dame cathedralin Paris on 16 December 1431, the boys tenth birthday. Before England could rebuild its military leadership and force of longbowmen lost in 1429, the country lost its alliance with Burgundy when theTreaty of Arraswas signed in 1435. The Duke of Bedford died the same year and Henry VI became the youngest king of England to rule without a regent. His weak leadership was probably the most important factor in ending the conflict. Kelly DeVries argues that Joan of Arcs aggressive use of artillery and frontal assaults influenced French tactics for the rest of the war.[93]

In 1452, during the posthumous investigation into her execution, the Church declared that a religious play in her honor at Orléans would allow attendees to gain anindulgence(remission of temporal punishment for sin) by making apilgrimageto the event.[citation needed]

Retrial

A posthumous retrial opened after the war ended.Pope Callixtus IIIauthorized this proceeding, also known as the "nullification trial", at the request of Inquisitor-GeneralJean Bréhaland Joans mother Isabelle Romée. The purpose of the trial was to investigate whether the trial of condemnation and its verdict had been handled justly and according to canon law. Investigations started with an inquest by Guillaume Bouillé, a theologian andformer rector of the University of Paris(Sorbonne). Bréhal conducted an investigation in 1452. A formal appeal followed in November 1455. The appellate process involved clergy from throughout Europe and observed standard court procedure. A panel of theologians analyzed testimony from 115 witnesses. Bréhal drew up his final summary in June 1456, which describes Joan as a martyr and implicated the late Pierre Cauchon with heresy[citation needed]for having convicted an innocent woman in pursuit of asecularvendetta. The technical reason for her execution had been a Biblical clothing law.[94]The nullification trial reversed the conviction in part because the condemnation proceeding had failed to consider the doctrinal exceptions to that stricture. The appellate court declared her innocent on 7 July 1456.[95]

Miniature fromVigiles du roi Charles VII. Joan and the king.

Joan of Arc depicted on horseback in an illustration from a 1505 manuscript.

Miniature fromVigiles du roi Charles VII. The assault on Paris.

Miniature fromVigiles du roi Charles VII. Joan being tied at the stake.

Canonization

Joan of Arc became a symbol of theCatholic Leagueduring the 16th century. WhenFélix Dupanloupwas made bishop of Orléans in 1849, he pronounced a fervidpanegyricon Joan of Arc, which attracted attention in England as well as France, and he led the efforts which culminated in Joan of Arcs beatification in 1909.[96]

Legacy

Joan of Arc became a semi-legendary figure for the four centuries after her death. The main sources of information about her were chronicles. Five original manuscripts of her condemnation trial surfaced in old archives during the 19th century. Soon, historians also located the complete records of her rehabilitation trial, which contained sworn testimony from 115 witnesses, and the original French notes for the Latin condemnation trial transcript. Various contemporary letters also emerged, three of which carry the signatureJehannein the unsteady hand of a person learning to write.[98]This unusual wealth of primary source material is one reason DeVries declares, "No person of the Middle Ages, male or female, has been the subject of more study."[99]

Joan of Arc came from an obscure village and rose to prominence when she was a teenager, and she did so as an uneducated peasant. The French and English kings had justified the ongoing war through competing interpretations of inheritance law, first concerning Edward IIIs claim to the French throne and then Henry VIs. The conflict had been a legalistic feud between two related royal families, but Joan transformed it along religious lines and gave meaning to appeals such as that of squire Jean de Metz when he asked, "Must the king be driven from the kingdom; and are we to be English?"[34]In the words of Stephen Richey, "She turned what had been a dry dynastic squabble that left the common people unmoved except for their own suffering into a passionately popular war of national liberation."[100]Richey also expresses the breadth of her subsequent appeal:

The people who came after her in the five centuries since her death tried to make everything of her: demonic fanatic, spiritual mystic, naive and tragically ill-used tool of the powerful, creator and icon of modern popular nationalism, adored heroine, saint. She insisted, even when threatened with torture and faced with death by fire, that she was guided by voices from God. Voices or no voices, her achievements leave anyone who knows her story shaking his head in amazed wonder.[100]

FromChristine de Pi" class="zoomMainImage swiper-slide"> DIMENSIONS: 490X 130 X 110mm. W . 3010 grs. Hundred Years War Joan of Arc(French:Jeanne dArc,[5]IPA:[ʒan daʁk]; 6 January c. 1412[6]– 30 May 1431), nicknamed "The Maid of Orléans" (French:La Pucelle dOrléans), is considered a heroine of France for her role during theLancastrian phaseof theHundred Years Warand was canonized as aRoman Catholic saint. Joan of Arc was born toJacques dArcandIsabelle Romée, apeasantfamily, atDomrémyin north-east France. Joan said she received visions of theArchangelMichael,Saint Margaret, andSaint Catherine of Alexandriainstructing her to supportCharles VIIand recover France from English domination late in the Hundred Years War. The uncrowned King Charles VII sent Joan to thesiege of Orléansas part of a relief mission. She gained prominence after the siege was lifted only nine days later. Several additional swift victories led to Charles VIIs coronation atReims. This long-awaited event boosted French morale and paved the way for the final French victory. On 23 May 1430, she was captured atCompiègneby theBurgundian faction, which was allied with the English. She was later handed over to the English[7]and put on trial by the pro-English Bishop of BeauvaisPierre Cauchonon a variety of charges.[8]After Cauchon declared her guilty she wasburned at the stakeon 30 May 1431, dying at about nineteen years of age.[9] In 1456, an inquisitorial court authorized byPope Callixtus IIIexamined the trial, debunked the charges against her, pronounced her innocent, and declared her amartyr.[9]In the 16th century she became a symbol of theCatholic League, and in 1803 she was declared a national symbol of France by the decision ofNapoleonBonaparte.[10]She wasbeatifiedin 1909 andcanonizedin 1920. Joan of Arc is one of the nine secondarypatron saintsof France, along withSaint Denis,Saint Martin of Tours,Saint Louis,Saint Michael,Saint Rémi,Saint Petronilla,Saint RadegundandSaint Thérèse of Lisieux. Joan of Arc has remained a popular figure in literature, painting, sculpture, and other cultural works since the time of her death, and many famous writers, filmmakers and composers have created works about her.Cultural depictions of herhave continued in films, theater, television, video games, music, and performances to this day. TheHundred Years Warhad begun in 1337 as aninheritance dispute over the French throne, interspersed with occasional periods of relative peace. Nearly all the fighting had taken place in France, and the English armys use ofchevauchéetactics (destructive "scorched earth" raids) had devastated the economy.[11]TheFrench populationhad not recovered to its size previous to theBlack Deathof the mid-14th century, and its merchants were isolated from foreign markets. Prior to the appearance of Joan of Arc, the English had nearly achieved their goal of a dual monarchy under English control and the French army had not achieved any major victories for a generation. In the words of DeVries, "The kingdom of France was not even a shadow of its thirteenth-century prototype."[12] The French king at the time of Joans birth,Charles VI, suffered from bouts of insanity[13]and was often unable to rule. The kings brotherLouis,Duke of Orléans, and the kings cousinJohn the Fearless,Duke of Burgundy, quarreled over the regency of France and the guardianship of the royal children. This dispute included accusations that Louis was having an extramarital affair with the queen,Isabeau of Bavaria, and allegations that John the Fearless kidnapped the royal children.[14]The conflict climaxed with the assassination of the Duke of Orléans in 1407 on the orders of the Duke of Burgundy.[15][16] The young Charles of Orléans succeeded his father as duke and was placed in the custody of his father-in-law, theCount of Armagnac. Their faction became known as the"Armagnac" faction, and the opposing party led by the Duke of Burgundy was called the"Burgundian faction".Henry V of Englandtook advantage of these internal divisions when he invaded the kingdom in 1415, winning a dramaticvictory at Agincourton 25 October and subsequently capturing many northern French towns.[17]In 1418Pariswas taken by the Burgundians, who massacred the Count of Armagnac and about 2,500 of his followers.[18]The future French king,Charles VII, assumed the title ofDauphin—the heir to the throne—at the age of fourteen, after all four of his older brothers had died in succession.[19]His first significant official act was to conclude a peace treaty with the Duke of Burgundy in 1419. This ended in disaster when Armagnac partisans assassinated John the Fearless during a meeting under Charless guarantee of protection. The new duke of Burgundy,Philip the Good, blamed Charles for the murder and entered into an alliance with the English. The allied forces conquered large sections of France.[20] In 1420 the queen of France,Isabeau of Bavaria, signed theTreaty of Troyes, which granted the succession of the French throne toHenry Vand his heirs instead of her son Charles. This agreement revived suspicions that the Dauphin may have been the illegitimate product of Isabeaus rumored affair with the late duke of Orléans rather than the son of King Charles VI.[21]Henry V and Charles VI died within two months of each other in 1422, leaving an infant,Henry VI of England, the nominal monarch of both kingdoms. Henry Vs brother,John of Lancaster, 1st Duke of Bedford, acted asregent.[22] By the time Joan of Arc began to influence events in 1429, nearly all of northern France and some parts of the southwest were under Anglo-Burgundian control. The English controlled Paris andRouenwhile the Burgundian faction controlledReims, which had served as the traditional coronation site for French kings since 816. This was an important consideration since neither claimant to the throne of France had been officially crowned yet. In 1428 the English had begun the siege of Orléans, one of the few remaining cities still loyal to Charles VII and an important objective since it held a strategic position along theLoireRiver, which made it the last obstacle to an assault on the remainder of the French heartland. In the words of one modern historian, "On the fate of Orléans hung that of the entire kingdom."[23]No one was optimistic that the city could long withstand the siege.[24]For generations, there had been prophecies in France which promised France would be saved by a virgin from the "borders of Lorraine" "who would work miracles" and "that France will be lost by a woman and shall thereafter be restored by a virgin".[25]The second prophecy predicating France would be "lost" by a woman was taken to refer to Isabeaus role in signing the Treaty of Troyes.[26] Joan was the daughter ofJacques dArcandIsabelle Romée[27]inDomrémy, a village which was then in the French part of theduchy of Bar.[28]Joans parents owned about 50 acres (20 hectares) of land and her father supplemented his farming work with a minor position as a village official, collecting taxes and heading the local watch.[29]They lived in an isolated patch of eastern France that remained loyal to the French crown despite being surrounded by pro-Burgundian lands. Several local raids occurred during her childhood and on one occasion her village was burned. Joan was illiterate and it is believed that her letters were dictated by her to scribes and she signed her letters with the help of others.[30] At her trial, Joan stated that she was about nineteen years old, which implies she thought she was born around 1412. She later testified that she experienced her first vision in 1425 at the age of 13, when she was in her "fathers garden"[31]and saw visions of figures she identified asSaint Michael,Saint Catherine, andSaint Margaret, who told her to drive out the English and bring the Dauphin to Reims for his coronation. She said she cried when they left, as they were so beautiful.[32] At the age of sixteen, she asked a relative named Durand Lassois to take her to the nearby town ofVaucouleurs, where she petitioned the garrison commander,Robert de Baudricourt, for an armed escort to bring her to the French Royal Court atChinon. Baudricourts sarcastic response did not deter her.[33]She returned the following January and gained support from two of Baudricourts soldiers:Jean de MetzandBertrand de Poulengy.[34]According to Jean de Metz, she told him that "I must be at the Kings side... there will be no help (for the kingdom) if not from me. Although I would rather have remained spinning [wool] at my mothers side... yet must I go and must I do this thing, for my Lord wills that I do so."[35]Under the auspices of Metz and Poulengy, she was given a second meeting, where she made a prediction about a military reversal at theBattle of Rouvraynear Orléans several days before messengers arrived to report it.[36]According to theJournal du Siége d’Orléans,which portrays Joan as a miraculous figure, Joan came to know of the battle through "grace divine" while tending her flocks in Lorraine and used this divine revelation to persuade Baudricort to take her to the Dauphin.[37] Robert de Baudricourt granted Joan an escort to visit Chinon after news from Orleans confirmed her assertion of the defeat. She made the journey through hostile Burgundian territory disguised as a male soldier,[38]a fact which would later lead to charges of "cross-dressing" against her, although her escort viewed it as a normal precaution. Two of the members of her escort said they and the people of Vaucouleurs provided her with this clothing, and had suggested it to her.[39] After arriving at the Royal Court she impressed Charles VII during a private conference. During this time Charles mother-in-lawYolande of Aragonwas planning to finance a relief expedition toOrléans. Joan asked for permission to travel with the army and wear protective armor, which was provided by the Royal government. She depended on donated items for her armor, horse, sword, banner, and other items utilized by her entourage. Historian Stephen W. Richey explains her attraction to the royal court by pointing out that they may have viewed her as the only source of hope for a regime that was near collapse: After years of one humiliating defeat after another, both the military and civil leadership of France were demoralized and discredited. When the Dauphin Charles granted Joans urgent request to be equipped for war and placed at the head of his army, his decision must have been based in large part on the knowledge that every orthodox, every rational option had been tried and had failed. Only a regime in the final straits of desperation would pay any heed to an illiterate farm girl who claimed that the voice of God was instructing her to take charge of her countrys army and lead it to victory.[40] Upon her arrival, Joan effectively turned the longstanding Anglo-French conflict into a religious war,[41]a course of action that was not without risk. Charles advisers were worried that unless Joansorthodoxycould be established beyond doubt—that she was not a heretic or a sorceress—Charles enemies could easily make the allegation that his crown was a gift from the devil. To circumvent this possibility, the Dauphin ordered background inquiries and a theological examination atPoitiersto verify her morality. In April 1429, the commission of inquiry "declared her to be of irreproachable life, a good Christian, possessed of the virtues of humility, honesty and simplicity."[41]The theologians at Poitiers did not render a decision on the issue of divine inspiration; rather, they informed the Dauphin that there was a "favorable presumption" to be made on the divine nature of her mission. This was enough for Charles, but they also stated that he had an obligation to put Joan to the test. "To doubt or abandon her without suspicion of evil would be to repudiate theHoly Spiritand to become unworthy of Gods aid", they declared.[42]They recommended that her claims should be put to the test by seeing if she could lift the siege ofOrléansas she had predicted.[citation needed] She arrived at thebesieged city of Orléanson 29 April 1429.Jean dOrléans, the acting head of the ducal family of Orléans on behalf of his captive half-brother, initially excluded her fromwar councilsand failed to inform her when the army engaged the enemy.[43]However, his decision to exclude her did not prevent her presence at most councils and battles.[citation needed] The extent of her actual military participation and leadership is a subject of debate among historians. On the one hand, Joan stated that she carried her banner in battle and had never killed anyone,[44]preferring her banner "forty times" better than a sword;[45]and the army was always directly commanded by a nobleman, such as the Duke of Alençon for example. On the other hand, many of these same noblemen stated that Joan had a profound effect on their decisions since they often accepted the advice she gave them, believing her advice was divinely inspired.[46]In either case, historians agree that the army enjoyed remarkable success during her brief time with it.[47] The appearance of Joan of Arc at Orléans coincided with a sudden change in the pattern of the siege. During the five months before her arrival, the defenders had attempted only one offensive assault, which had ended in defeat. On 4 May, however, the Armagnacs attacked and captured the outlying fortress ofSaint Loup(bastille de Saint-Loup), followed on 5 May by a march to a second fortress calledSaint-Jean-le-Blanc, which was found deserted. When English troops came out to oppose the advance, a rapid cavalry charge drove them back into their fortresses, apparently without a fight. The Armagnacs then attacked and captured an English fortress built around a monastery calledLes Augustins. That night, Armagnac troops maintained positions on the south bank of the river before attacking the main English stronghold, called"les Tourelles", on the morning of 7 May.[49]Contemporaries acknowledged Joan as the heroine of the engagement. She was wounded by an arrow between the neck and shoulder while holding her banner in the trench outside les Tourelles, but later returned to encourage a final assault that succeeded in taking the fortress. The English retreated from Orléans the next day, and the siege was over.[citation needed] At Chinon and Poitiers, Joan had declared that she would provide a sign at Orléans. The lifting of the siege was interpreted by many people to be that sign, and it gained her the support of prominent clergy such as theArchbishop of Embrunand the theologianJean Gerson, both of whom wrote supportive treatises immediately following this event.[50]To the English, the ability of this peasant girl to defeat their armies was regarded as proof that she was possessed by the Devil; the British medievalist Beverly Boyd noted that this charge was not just propaganda, and was sincerely believed since the idea that God was supporting the French via Joan was distinctly unappealing to an English audience.[51] The sudden victory at Orléans also led to many proposals for further offensive action. Joan persuaded Charles VII to allow her to accompany the army with DukeJohn II of Alençon, and she gained royal permission for her plan to recapture nearby bridges along the Loire as a prelude to an advance on Reims and the coronation of Charles VII. This was a bold proposal because Reims was roughly twice as far away as Paris and deep within enemy territory.[52]The English expected an attempt to recapture Paris or an attack on Normandy.[citation needed] The Duke of Alençon accepted Joans advice concerning strategy. Other commanders including Jean dOrléans had been impressed with her performance at Orléans and became her supporters. Alençon credited her with saving his life at Jargeau, where she warned him that a cannon on the walls was about to fire at him.[53]During the same siege she withstood a blow from a stone that hit her helmet while she was near the base of the towns wall. The army tookJargeauon 12 June,Meung-sur-Loireon 15 June, andBeaugencyon 17 June.[citation needed] The English army withdrew from the Loire Valley and headed north on 18 June, joining with an expected unit of reinforcements under the command of SirJohn Fastolf. Joan urged the Armagnacs to pursue, and the two armies clashed southwest of the village of Patay. Thebattle at Pataymight be compared toAgincourtin reverse. The French vanguard attacked a unit of Englisharcherswho had been placed to block the road. A rout ensued that decimated the main body of the English army and killed or captured most of its commanders. Fastolf escaped with a small band of soldiers and became the scapegoat for the humiliating English defeat. The French suffered minimal losses.[54] The French army leftGienon 29 June on themarch toward Reimsand accepted the conditional surrender of the Burgundian-held city ofAuxerreon 3 July. Other towns in the armys path returned to French allegiance without resistance.Troyes, the site of the treaty that tried to disinherit Charles VII, was the only one to put up even brief opposition. The army was in short supply of food by the time it reached Troyes. But the army was in luck: a wandering friar named Brother Richard had been preaching about the end of the world at Troyes and convinced local residents to plant beans, a crop with an early harvest. The hungry army arrived as the beans ripened.[55]Troyes capitulated after a bloodless four-day siege.[56] Reims opened its gates to the army on 16 July 1429. The coronation took place the following morning. Although Joan and the Duke of Alençon urged a prompt march on Paris, the royal court preferred to negotiate a truce with Duke Philip of Burgundy. The duke violated the purpose of the agreement by using it as a stalling tactic to reinforce the defense of Paris.[57]The French army marched through towns near Paris during the interim and accepted several peaceful surrenders. The Duke of Bedford led an English force and confronted the French army in a standoff at the battle of Montépilloy on 15 August. The Frenchassault at Parisensued on 8 September. Despite a wound to the leg from acrossbow bolt, Joan remained in the inner trench of Paris until she was carried back to safety by one of the commanders.[58]The following morning the army received a royal order to withdraw. Most historians blame FrenchGrand ChamberlainGeorges de la Trémoillefor the political blunders that followed the coronation.[59]In October, Joan was with the royal army when ittook Saint-Pierre-le-Moûtier, followed by an unsuccessful attempt to takeLa-Charité-sur-Loirein November and December. On 29 December, Joan and her family were ennobled by Charles VII as a reward for her actions.[citation needed] Ruin of the great hall atChâteau de Chinonwhere Joan met future King Charles VII. The castles only remaining intact tower, now known as the Joan of Arc Tower, has been turned into a museum dedicated to her. Entrance of Joan of Arc into Reims in 1429, painting byJan Matejko The inner keep atBeaugencyis one of the few surviving fortifications from Joans campaigns. English defenders retreated to the tower at upper right after the French breached the town wall. Notre-Dame de Reims, traditional site of French coronations. The structure had additional spires prior to a 1481 fire. A truce with England during the following few months left Joan with little to do. On 23 March 1430, she dictated a threatening letter to theHussites, a dissident group which had broken with the Catholic Church on a number of doctrinal points and had defeated several previous crusades sent against them. Joans letter promises to "remove your madness and foul superstition, taking away either your heresy or your lives."[60]Joan, an ardent Catholic who hated all forms of heresy together with Islam also sent a letter challenging the English to leave France and go with her to Bohemia to fight the Hussites, an offer that went unanswered.[61] The truce with England quickly came to an end. Joan traveled toCompiègnethe following May to help defend the city against anEnglish and Burgundian siege. On 23 May 1430 she was with a force that attempted to attack the Burgundian camp at Margny north of Compiègne, but was ambushed and captured.[62]When the troops began to withdraw toward the nearby fortifications of Compiègne after the advance of an additional force of 6,000 Burgundians,[62]Joan stayed with the rear guard. Burgundian troops surrounded the rear guard, and she was pulled off her horse by anarcher.[63]She agreed to surrender to a pro-Burgundian nobleman named Lionel of Wandomme, a member ofJean de Luxembourgs unit.[citation needed] Joan was imprisoned by the Burgundians at Beaurevoir Castle. She made several escape attempts, on one occasion jumping from her 70-foot (21m) tower, landing on the soft earth of a dry moat, after which she was moved to the Burgundian town ofArras.[64]The English negotiated with their Burgundian allies to transfer her to their custody, with BishopPierre CauchonofBeauvais, an English partisan, assuming a prominent role in these negotiations and her later trial.[65]The final agreement called for the English to pay the sum of 10,000livres tournois[66]to obtain her from Jean de Luxembourg, a member of the Council of Duke Philip of Burgundy.[citation needed] The English moved Joan to the city of Rouen, which served as their main headquarters in France. Historian Pierre Champion notes that the Armagnacs attempted to rescue her several times by launching military campaigns toward Rouen while she was held there. One campaign occurred during the winter of 1430–1431, another in March 1431, and one in late May shortly before her execution. These attempts were beaten back.[67]Champion also quotes 15th-century sources that say Charles VII threatened to "exact vengeance" upon Burgundian troops whom his forces had captured and upon "the English and women of England" in retaliation for their treatment of Joan.[68] The trial forheresywas politically motivated. The tribunal was composed entirely of pro-English and Burgundian clerics, and overseen by English commanders including the Duke of Bedford and the Earl of Warwick.[69]In the words of the British medievalist Beverly Boyd, the trial was meant by the English Crown to be "...a ploy to get rid of a bizarre prisoner of war with maximum embarrassment to their enemies".[51]Legal proceedings commenced on 9 January 1431 atRouen, the seat of the English occupation government.[70]The procedure was suspect on a number of points, which would later provoke criticism of the tribunal by the chief inquisitor who investigated the trial after the war.[71] Under ecclesiastical law, Bishop Cauchon lackedjurisdictionover the case.[72]Cauchon owed his appointment to his partisan support of the English Crown, which financed the trial. The low standard of evidence used in the trial also violated inquisitorial rules.[73]Clerical notary Nicolas Bailly, who was commissioned to collect testimony against Joan, could find no adverse evidence.[74]Without such evidence the court lacked grounds to initiate a trial. Opening a trial anyway, the court also violated ecclesiastical law by denying Joan the right to a legal adviser. In addition, stacking the tribunal entirely with pro-English clergy violated the medieval Churchs requirement that heresy trials be judged by an impartial or balanced group of clerics. Upon the opening of the first public examination, Joan complained that those present were all partisans against her and asked for "ecclesiastics of the French side" to be invited in order to provide balance. This request was denied.[75] The Vice-Inquisitor of Northern France (Jean Lemaitre) objected to the trial at its outset, and several eyewitnesses later said he was forced to cooperate after the English threatened his life.[76]Some of the other clergy at the trial were also threatened when they refused to cooperate, including a Dominican friar named Isambart de la Pierre.[77]These threats, and the domination of the trial by a secular government, were violations of the Churchs rules and undermined the right of the Church to conduct heresy trials without secular interference.[citation needed] The trial record contains statements from Joan that the eyewitnesses later said astonished the court, since she was an illiterate peasant and yet was able to evade the theological pitfalls the tribunal had set up to entrap her. The transcripts most famous exchange is an exercise in subtlety: "Asked if she knew she was in Gods grace, she answered, If I am not, may God put me there; and if I am, may God so keep me."[78]The question is a scholarly trap. Church doctrine held that no one could be certain of being in Gods grace. If she had answered yes, then she would have been charged with heresy. If she had answered no, then she would have confessed her own guilt. The court notary Boisguillaume later testified that at the moment the court heard her reply, "Those who were interrogating her were stupefied."[79] Several members of the tribunal later testified that important portions of the transcript were falsified by being altered in her disfavor. Under Inquisitorial guidelines, Joan should have been confined in anecclesiasticalprison under the supervision of female guards (i.e., nuns). Instead, the English kept her in asecularprison guarded by their own soldiers. Bishop Cauchon denied Joans appeals to theCouncil of Baseland the Pope, which should have stopped his proceeding.[80] The twelve articles of accusation which summarized the courts findings contradicted the already doctored court record.[81]The illiterate defendant signed anabjurationdocument that she did not understand under threat of immediate execution. The court substituted a different abjuration in the official record.[82] Heresywas acapital crimeonly for a repeat offense, therefore a repeat offense of "cross-dressing" was now arranged by the court, according to the eyewitnesses. Joan agreed to wear feminine clothing when she abjured, which created a problem. According to the later descriptions of some of the tribunal members, she had previously been wearing male (i.e. military) clothing in prison because it gave her the ability to fasten her hosen, boots and tunic together into one piece, which deterred rape by making it difficult to pull her hosen off. She was evidently afraid to give up this outfit even temporarily because it was likely to be confiscated by the judge and she would thereby be left without protection.[83][84]A womans dress offered no such protection. A few days after her abjuration, when she was forced to wear a dress, she told a tribunal member that "a great English lord had entered her prison and tried to take her by force."[85]She resumed male attire either as a defense against molestation or, in the testimony of Jean Massieu, because her dress had been taken by the guards and she was left with nothing else to wear.[86] Her resumption of male military clothing was labeled a relapse into heresy for cross-dressing, although this would later be disputed by the inquisitor who presided over the appeals court that examined the case after the war. Medieval Catholic doctrine held that cross-dressing should be evaluated based on context, as stated in theSumma TheologicabySt. Thomas Aquinas, which says that necessity would be a permissible reason for cross-dressing.[87]This would include the use of clothing as protection against rape if the clothing would offer protection. In terms of doctrine, she had been justified in disguising herself as a pageboy during her journey through enemy territory, and she was justified in wearing armor during battle and protective clothing in camp and then in prison. TheChronique de la Pucellestates that it deterred molestation while she was camped in the field. When her soldiers clothing wasnt needed while on campaign, she was said to have gone back to wearing a dress.[88]Clergy who later testified at the posthumous appellate trial affirmed that she continued to wear male clothing in prison to deter molestation and rape.[83] Joan referred the court to the Poitiers inquiry when questioned on the matter. The Poitiers record no longer survives, but circumstances indicate the Poitiers clerics had approved her practice.[89]She also kept her hair cut short through her military campaigns and while in prison. Her supporters, such as the theologianJean Gerson, defended her hairstyle for practical reasons, as did Inquisitor Brehal later during the appellate trial.[90]Nonetheless, at the trial in 1431 she was condemned and sentenced to die. Boyd described Joans trial as so "unfair" that the trial transcripts were later used as evidence for canonizing her in the 20th century.[51] Eyewitnesses described the scene of theexecution by burningon 30 May 1431. Tied to a tall pillar at the Vieux-Marché in Rouen, she asked two of the clergy, Fr Martin Ladvenu and Fr Isambart de la Pierre, to hold acrucifixbefore her. An English soldier also constructed a small cross that she put in the front of her dress. After she died, the English raked back the coals to expose her charred body so that no one could claim she had escaped alive. They then burned the body twice more, to reduce it to ashes and prevent any collection of relics, and cast her remains into theSeineRiver.[91]The executioner, Geoffroy Thérage, later stated that he "greatly feared to be damned."[92] The Hundred Years War continued for twenty-two years after her death. Charles VII retained legitimacy as the king of France in spite of a rival coronation held forHenry VIatNotre-Dame cathedralin Paris on 16 December 1431, the boys tenth birthday. Before England could rebuild its military leadership and force of longbowmen lost in 1429, the country lost its alliance with Burgundy when theTreaty of Arraswas signed in 1435. The Duke of Bedford died the same year and Henry VI became the youngest king of England to rule without a regent. His weak leadership was probably the most important factor in ending the conflict. Kelly DeVries argues that Joan of Arcs aggressive use of artillery and frontal assaults influenced French tactics for the rest of the war.[93] In 1452, during the posthumous investigation into her execution, the Church declared that a religious play in her honor at Orléans would allow attendees to gain anindulgence(remission of temporal punishment for sin) by making apilgrimageto the event.[citation needed] A posthumous retrial opened after the war ended.Pope Callixtus IIIauthorized this proceeding, also known as the "nullification trial", at the request of Inquisitor-GeneralJean Bréhaland Joans mother Isabelle Romée. The purpose of the trial was to investigate whether the trial of condemnation and its verdict had been handled justly and according to canon law. Investigations started with an inquest by Guillaume Bouillé, a theologian andformer rector of the University of Paris(Sorbonne). Bréhal conducted an investigation in 1452. A formal appeal followed in November 1455. The appellate process involved clergy from throughout Europe and observed standard court procedure. A panel of theologians analyzed testimony from 115 witnesses. Bréhal drew up his final summary in June 1456, which describes Joan as a martyr and implicated the late Pierre Cauchon with heresy[citation needed]for having convicted an innocent woman in pursuit of asecularvendetta. The technical reason for her execution had been a Biblical clothing law.[94]The nullification trial reversed the conviction in part because the condemnation proceeding had failed to consider the doctrinal exceptions to that stricture. The appellate court declared her innocent on 7 July 1456.[95] Miniature fromVigiles du roi Charles VII. Joan and the king. Joan of Arc depicted on horseback in an illustration from a 1505 manuscript. Miniature fromVigiles du roi Charles VII. The assault on Paris. Miniature fromVigiles du roi Charles VII. Joan being tied at the stake. Joan of Arc became a symbol of theCatholic Leagueduring the 16th century. WhenFélix Dupanloupwas made bishop of Orléans in 1849, he pronounced a fervidpanegyricon Joan of Arc, which attracted attention in England as well as France, and he led the efforts which culminated in Joan of Arcs beatification in 1909.[96] Joan of Arc became a semi-legendary figure for the four centuries after her death. The main sources of information about her were chronicles. Five original manuscripts of her condemnation trial surfaced in old archives during the 19th century. Soon, historians also located the complete records of her rehabilitation trial, which contained sworn testimony from 115 witnesses, and the original French notes for the Latin condemnation trial transcript. Various contemporary letters also emerged, three of which carry the signatureJehannein the unsteady hand of a person learning to write.[98]This unusual wealth of primary source material is one reason DeVries declares, "No person of the Middle Ages, male or female, has been the subject of more study."[99] Joan of Arc came from an obscure village and rose to prominence when she was a teenager, and she did so as an uneducated peasant. The French and English kings had justified the ongoing war through competing interpretations of inheritance law, first concerning Edward IIIs claim to the French throne and then Henry VIs. The conflict had been a legalistic feud between two related royal families, but Joan transformed it along religious lines and gave meaning to appeals such as that of squire Jean de Metz when he asked, "Must the king be driven from the kingdom; and are we to be English?"[34]In the words of Stephen Richey, "She turned what had been a dry dynastic squabble that left the common people unmoved except for their own suffering into a passionately popular war of national liberation."[100]Richey also expresses the breadth of her subsequent appeal: The people who came after her in the five centuries since her death tried to make everything of her: demonic fanatic, spiritual mystic, naive and tragically ill-used tool of the powerful, creator and icon of modern popular nationalism, adored heroine, saint. She insisted, even when threatened with torture and faced with death by fire, that she was guided by voices from God. Voices or no voices, her achievements leave anyone who knows her story shaking his head in amazed wonder.[100] FromChristine de Pi" alt="† SAINTE JEANNE D'ARC GRANDE STATUE soldes EN PLÂTRE PEINT BRONZE SIGNÉE SALVETTI FRANCE †" width="527" height="527" />Joan of Arc

Saint Joan of Arc

Virgin and Martyr Born 6 January c. 1412[2]

Domrémy,Duchy of Bar,Kingdom of France[3]Died 30 May 1431 (aged approx. 19)

Rouen,Normandy

(thenunder English rule)Veneratedin Roman Catholic Church

Anglican Communion[4]Beatified 18 April 1909,Notre Dame de ParisbyPope Pius X Canonized 16 May 1920,St. Peters Basilica, Rome byPope Benedict XV Feast 30 May Attributes armor, banner,sword Patronage France; martyrs; captives; military personnel; people ridiculed for their piety; prisoners; soldiers, women who have served in theWAVES(Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service); andWomens Army Corps Native name Jeanne dArc Nickname(s) La Pucelle

The Maid of Orléans

(French:La Pucelle dOrléans)Allegiance ![]() Kingdom of France

Kingdom of FranceYearsof service 1428–1430 Battles/wars Signature

Background

Life

Rise

Military campaigns

Capture

Trial

Cross-dressing charge

Execution

Posthumous events

Retrial

Canonization

Legacy

† SAINTE JEANNE D'ARC GRANDE STATUE soldes EN PLÂTRE PEINT BRONZE SIGNÉE SALVETTI FRANCE †

† SAINTE JEANNE D'ARC GRANDE STATUE soldes EN PLÂTRE PEINT BRONZE SIGNÉE SALVETTI FRANCE †, † SAINTE JEANNE D'ARC GRANDE STATUE EN PLÂTRE PEINT BRONZE SIGNÉE SALVETTI FRANCE † économies

SKU: 9012864

- SAINT JOAN of ARCJEANNE DARC au FLAMBEAUBRONZE PAINTED PLASTERCHALKWARESigned T.SALVETTI - MULHOUSEfrom FRANCEPERIOD 1900s

DIMENSIONS:

490X 130 X 110mm.

W . 3010 grs.

Joan of Arc

Saint Joan of Arc  Miniature (15th century)[1]

Miniature (15th century)[1]Virgin and Martyr Born 6 January c. 1412[2]

Domrémy,Duchy of Bar,Kingdom of France[3]Died 30 May 1431 (aged approx. 19)

Rouen,Normandy

(thenunder English rule)Veneratedin Roman Catholic Church

Anglican Communion[4]Beatified 18 April 1909,Notre Dame de ParisbyPope Pius X Canonized 16 May 1920,St. Peters Basilica, Rome byPope Benedict XV Feast 30 May Attributes armor, banner,sword Patronage France; martyrs; captives; military personnel; people ridiculed for their piety; prisoners; soldiers, women who have served in theWAVES(Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service); andWomens Army Corps Native name Jeanne dArc Nickname(s) La Pucelle

The Maid of Orléans

(French:La Pucelle dOrléans)Allegiance  Kingdom of France

Kingdom of FranceYearsof service 1428–1430 Battles/wars Hundred Years War

- Loire Campaign:

- Siege of Orléans

- Battle of Jargeau

- Battle of Meung-sur-Loire

- Battle of Beaugency

- Battle of Patay

- March to Reims

- Siege of Paris

- Siege of La Charité

- Siege of Compiègne

Signature

Joan of Arc(French:Jeanne dArc,[5]IPA:[ʒan daʁk]; 6 January c. 1412[6]– 30 May 1431), nicknamed "The Maid of Orléans" (French:La Pucelle dOrléans), is considered a heroine of France for her role during theLancastrian phaseof theHundred Years Warand was canonized as aRoman Catholic saint. Joan of Arc was born toJacques dArcandIsabelle Romée, apeasantfamily, atDomrémyin north-east France. Joan said she received visions of theArchangelMichael,Saint Margaret, andSaint Catherine of Alexandriainstructing her to supportCharles VIIand recover France from English domination late in the Hundred Years War. The uncrowned King Charles VII sent Joan to thesiege of Orléansas part of a relief mission. She gained prominence after the siege was lifted only nine days later. Several additional swift victories led to Charles VIIs coronation atReims. This long-awaited event boosted French morale and paved the way for the final French victory.

On 23 May 1430, she was captured atCompiègneby theBurgundian faction, which was allied with the English. She was later handed over to the English[7]and put on trial by the pro-English Bishop of BeauvaisPierre Cauchonon a variety of charges.[8]After Cauchon declared her guilty she wasburned at the stakeon 30 May 1431, dying at about nineteen years of age.[9]

In 1456, an inquisitorial court authorized byPope Callixtus IIIexamined the trial, debunked the charges against her, pronounced her innocent, and declared her amartyr.[9]In the 16th century she became a symbol of theCatholic League, and in 1803 she was declared a national symbol of France by the decision ofNapoleonBonaparte.[10]She wasbeatifiedin 1909 andcanonizedin 1920. Joan of Arc is one of the nine secondarypatron saintsof France, along withSaint Denis,Saint Martin of Tours,Saint Louis,Saint Michael,Saint Rémi,Saint Petronilla,Saint RadegundandSaint Thérèse of Lisieux.

Joan of Arc has remained a popular figure in literature, painting, sculpture, and other cultural works since the time of her death, and many famous writers, filmmakers and composers have created works about her.Cultural depictions of herhave continued in films, theater, television, video games, music, and performances to this day.

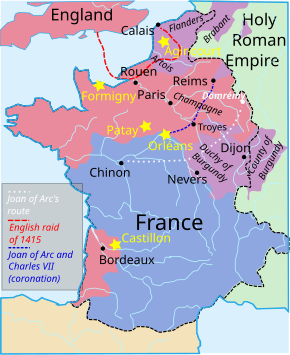

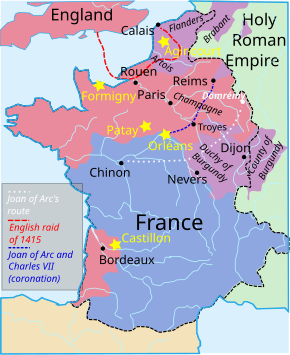

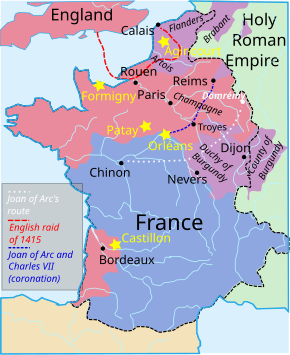

Background

1415–1429Territories controlled byHenry VI of EnglandTerritories controlled byPhilip III of BurgundyTerritories controlled byCharles VII of FranceMain battlesEnglish raid of 1415Joans journey from Domrémy toChinonRaid of Jeanne dArc toReimsin 1429

1415–1429Territories controlled byHenry VI of EnglandTerritories controlled byPhilip III of BurgundyTerritories controlled byCharles VII of FranceMain battlesEnglish raid of 1415Joans journey from Domrémy toChinonRaid of Jeanne dArc toReimsin 1429TheHundred Years Warhad begun in 1337 as aninheritance dispute over the French throne, interspersed with occasional periods of relative peace. Nearly all the fighting had taken place in France, and the English armys use ofchevauchéetactics (destructive "scorched earth" raids) had devastated the economy.[11]TheFrench populationhad not recovered to its size previous to theBlack Deathof the mid-14th century, and its merchants were isolated from foreign markets. Prior to the appearance of Joan of Arc, the English had nearly achieved their goal of a dual monarchy under English control and the French army had not achieved any major victories for a generation. In the words of DeVries, "The kingdom of France was not even a shadow of its thirteenth-century prototype."[12]

The French king at the time of Joans birth,Charles VI, suffered from bouts of insanity[13]and was often unable to rule. The kings brotherLouis,Duke of Orléans, and the kings cousinJohn the Fearless,Duke of Burgundy, quarreled over the regency of France and the guardianship of the royal children. This dispute included accusations that Louis was having an extramarital affair with the queen,Isabeau of Bavaria, and allegations that John the Fearless kidnapped the royal children.[14]The conflict climaxed with the assassination of the Duke of Orléans in 1407 on the orders of the Duke of Burgundy.[15][16]

The young Charles of Orléans succeeded his father as duke and was placed in the custody of his father-in-law, theCount of Armagnac. Their faction became known as the"Armagnac" faction, and the opposing party led by the Duke of Burgundy was called the"Burgundian faction".Henry V of Englandtook advantage of these internal divisions when he invaded the kingdom in 1415, winning a dramaticvictory at Agincourton 25 October and subsequently capturing many northern French towns.[17]In 1418Pariswas taken by the Burgundians, who massacred the Count of Armagnac and about 2,500 of his followers.[18]The future French king,Charles VII, assumed the title ofDauphin—the heir to the throne—at the age of fourteen, after all four of his older brothers had died in succession.[19]His first significant official act was to conclude a peace treaty with the Duke of Burgundy in 1419. This ended in disaster when Armagnac partisans assassinated John the Fearless during a meeting under Charless guarantee of protection. The new duke of Burgundy,Philip the Good, blamed Charles for the murder and entered into an alliance with the English. The allied forces conquered large sections of France.[20]

In 1420 the queen of France,Isabeau of Bavaria, signed theTreaty of Troyes, which granted the succession of the French throne toHenry Vand his heirs instead of her son Charles. This agreement revived suspicions that the Dauphin may have been the illegitimate product of Isabeaus rumored affair with the late duke of Orléans rather than the son of King Charles VI.[21]Henry V and Charles VI died within two months of each other in 1422, leaving an infant,Henry VI of England, the nominal monarch of both kingdoms. Henry Vs brother,John of Lancaster, 1st Duke of Bedford, acted asregent.[22]